A piece of paper, a Ziplock bag, and a bit of courage - that's all you need.

By Rev. Chris Travers

OF ALL THE SOUNDS that fill a summer camp—the shouts of games in the main compound, the crunch of gravel underfoot, the crackle of the evening campfire, the sound of waves from the lake, and, of course, the sound of coming down the laneway into the thin place that is Camp Huron—it’s the quiet conversations that often hold the most power.

This summer, I tried something new in our Journeys sessions (Christian Education): a lesson that began with scripture and ancient history and ended with a Ziplock bag full of paper pieces, ready to be picked up by another cabin the following week.

Each session began with one of the children reading a story of the early disciples. We huddled together not in a stuffy classroom but in the space where we worship twice daily—the indoor chapel—and we leaned over a map, talking about what it must have been like to share the Good News. It wasn’t just sharing, though; we got specific.

“Imagine,” I asked the campers, “what risks were involved in travelling around with the most amazing, life-changing story?”

They listed all sorts of dangers, from dehydration and sore feet to capsized boats and bandits.

“Now, imagine you have to share it with a soldier from an army that’s occupying your town, a government that has the power to throw you in jail, or even hurt you for what you’re about to say.”

They thought deeply and listed other kinds of risks: rejection, ridicule, persecution. We talked about the courage it took to speak about Jesus in hostile, “occupied territory,” and what kind of message you must have to be willing to take all those risks.

Then, they received their own mission. They had to put together a package of notes for a cabin group that would come the following week. They would become disciples sharing Good News about God—and also sharing what not to miss during their time at camp.

“They might be nervous, or unsure, or just not know what this place is all about,” I explained, “so your task is to write them a message. Tell them what you want them to know about God, or about this camp. Be their ‘good news.’”

The results were astounding. The messages weren’t theological essays; they were pure, heartfelt testimony, with many recurring themes:

“God loves you. Don’t be afraid to be yourself here at Camp Huron. I hope you have lots of fun. Give everyone grace and forgiveness. Camp is a safe space.”

They were taking a small, safe risk—the risk of being vulnerable, of putting their faith into words for a stranger. They were, in their own way, understanding the disciples’ dilemma and courage.

Then, the following week, after the cabin finished their notes for the next group and went to collect the package left for them from one of many locations around the camp, came the most powerful part.

We opened the package together and read through the messages. The chapel was quiet as they listened to the words of those who had come before them.

The reactions were noticeable: a shy smile, a nod of agreement, a whispered or shouted “wow,” or “I hope we get to eat that, try that activity.” One camper said quietly, “I thought I was the only one who felt that way.” Another, listening intently, said, “It feels like they’re our friends, and we haven’t even met them.”

They weren’t just receiving a piece of advice; they were receiving a testament. They were experiencing the result of someone else’s courage to share. The notes bridged the gap between weeks and age groups, creating an instant, invisible community of faith—a part of something bigger. The new campers felt seen, welcomed, and loved.

In our debrief before the end of the session, we connected the dots. “How did you feel getting those notes?” I asked.

“Like someone cared about me,” one said.

“Like I belong here,” added another.

“It made me excited for the week.”

“And that,” I said, “is a tiny glimpse of what it feels like to receive the Good News. It’s a message of love and belonging passed down through generations, from people who took risks to make sure it reached you. Your note is your version of that. You are the disciples for the next cabin.”

The lesson was no longer just a history lesson but a lived experience. They learned that evangelism isn’t about having all the answers or being a perfect speaker; it’s about having an experience of God’s love so real that you can’t help but want to share it with the next person, even if it feels a little risky. It’s about leaving a message of hope for the ones who will come after us.

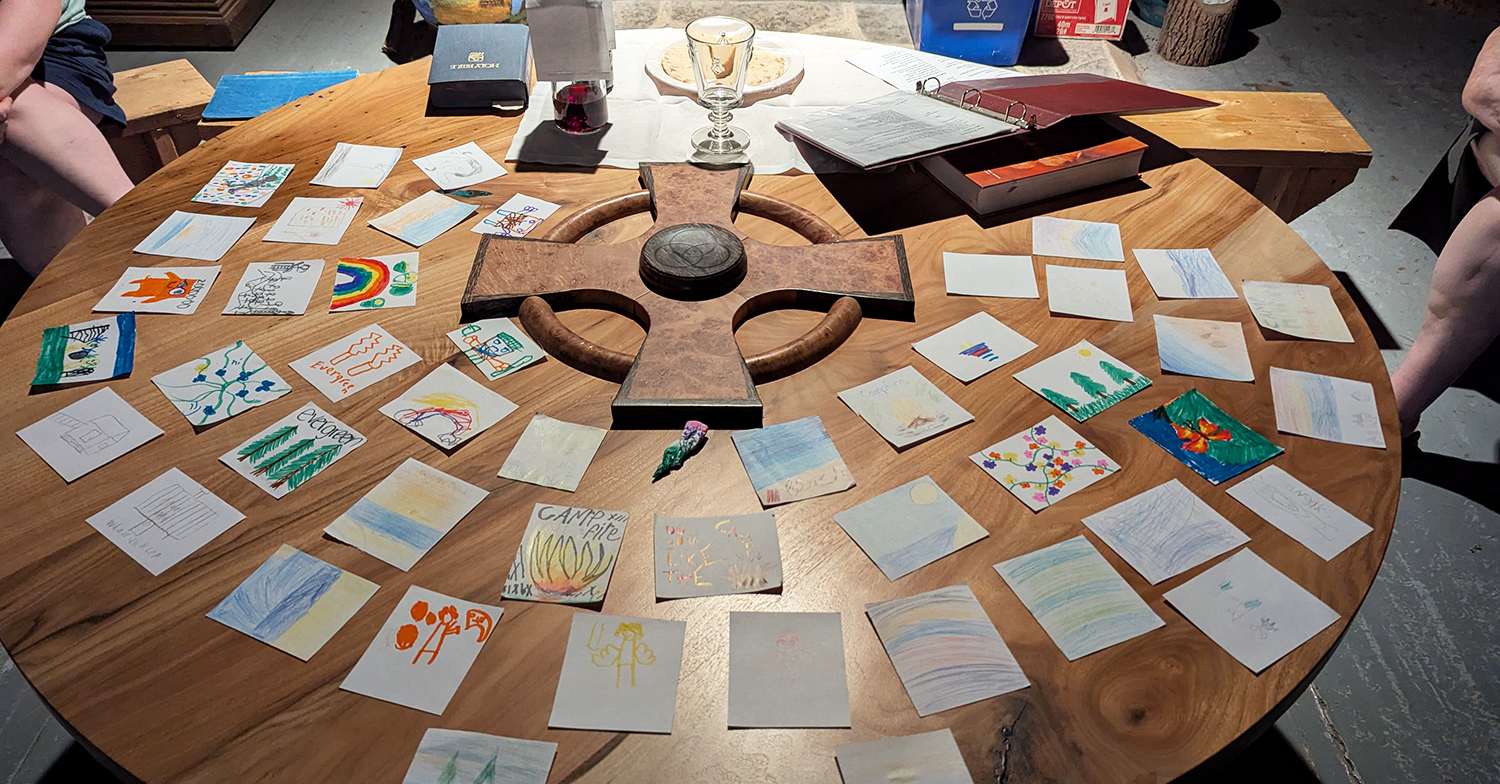

The final group of campers had the same experience, although their notes were directed toward the staff, to encourage us as we once again departed the sacred space. The artwork they left decorated the altar at our final Eucharist together, and the remaining notes formed the sermon—for what else could be said about our time together than what was written by those whom we had come together to serve this summer?

The sun has set on another summer at Camp Huron, and I like to think that the walls of the many gathering spaces are whispering with the accumulated prayers and encouragement of the young ones and the staff—each one learning that the most important things we can leave behind are love, courage, and a message of good news for the next traveller to come down that sacred laneway.

Rev. Chris Travers is Camp Huron's Chaplain.