By John Lutman

Recently, I have sent two archival items for conservation. The items comprise a set of three drawings for a “Synod House” in London, dated 1867, and an attendance register for the Mohawk Residential School in Brantford, dated 1859-1873 (a brief section comprises inspector’s reports).

The work was done respectively by professional conservators, Jennifer Robertson (Book and Paper Conservation Services) and Dan Mezza (Dan Mezza Bookbinding), both resident in London. This month’s article on the register comprises Part I; a subsequent month’s article will comprise Part II and will focus on the drawings.

From a rare book librarian’s or archivist’s perspective, conservation, whether for a book or a document, holds an important place in the policies and functions of a special collections or an archive.

The register, as it is bound in a similar manner to a book, is thus by definition a “book”. From the book perspective, conservation is a continuum from repair through restoration to the ultimate goal of conservation. Repair implies fixing a particular problem (a loose page or a tear) to keep the book stable thereby guarding it against further damage; restoration implies returning the book as near as possible to its original state using the skill of the conservator and tools of the trade; conservation has elements of restoration in its definition, but ultimately denotes the book’s final state on completion of restoration thereby conserving it for future use and protecting it from additional damage. A cardinal rule for book conservators is that the work undertaken must be reversible if it is determined that the materials used are causing further damage to the item.

The conservation of a book, however, as opposed to a document is an entirely different process. Different approaches to conservation are required as a book is a three dimensional object where a paper document is a two dimensional object. This difference will be apparent in the conservation strategies devised by Dan in Part I and Jennifer in Part II.

First, the register (Dan)

Mohawk Residential School Attendance Register

The goal that Dan set for himself was to return as much as possible the structure and appearance of the register to the 1870s, when it was new. Functionality is an additional goal. Will the book open? Is it usable?

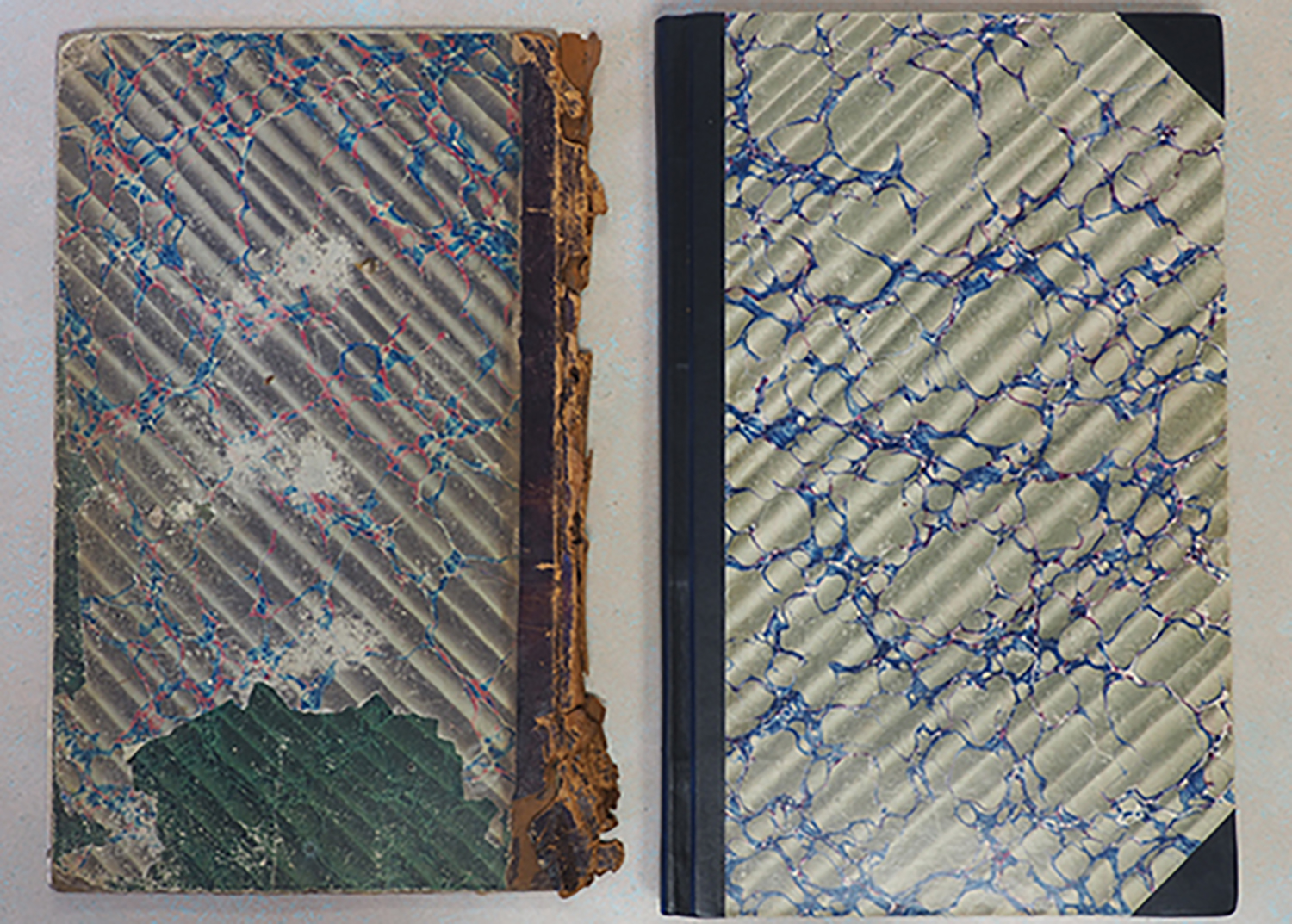

Mohawk Residential School attendance register – before and after

Initially, he determined that the register comprised a mid-nineteenth century stationary binding. To explain, there exists a marked distinction between letter press bindings used for reading and bindings for written matter or accounts known as stationary bindings.

The register’s stationary binding is interesting because it was put together from two or possibly three older ledgers. There are three distinct papers used. The oldest have entries dating from the 1850s. Other papers have watermarks (a distinguishing mark made on paper during its manufacture) dating from the 1860s with entries starting in 1870. The sewing structure on the spine of the ledger also shows that it was made from several older ledgers.

The ledger was in very poor condition (see illustration). Both the back and front boards were detached from the pages and the leather spine, which was disintegrating. The boards were also damaged at the corners and where they had been attached to the spine. There were also problems with the sewing; as well, the sections were coming apart (the paper of a book is gathered in sections and then sewn together).

The ledger was taken apart and the papers repaired as needed. Repairs were made to the back of the sections so that the ledger could be resewn on four linen tapes. New end papers were made (the blank pages at the front and back of a book). A new case was made (the outside of a book comprising boards back and front and a spine). In imitation of the original register, the structure included a spine of leather and boards covered in marble paper in a Spanish style that was made c. 1870. This gave the ledger the same appearance when first used.

Conservation work is costly, which is not surprising given the time devoted by the conservator to accessing the item, devising a treatment plan, and on the actual restoration of the item; added to this of course is the cost of materials used in the conservation process. An important factor worked into the cost reflects the conservator’s professional attainment – education, experience, reputation, and membership and participation in professional associations. The Archives, understandingly, can only afford to restore one or two items in a year, if that.

The conservation of an archival item be it a register, an architectural drawing, a 19th century property document or a parish register acts to conserve and protect them from further damage. Much depends thereafter on climate control, storage, and policies on access and handling policies of the archives. The diocesan archives has undertaken recently an effort to digitize its more fragile holdings which, because of their precarious condition (mostly due to crumbling paper), can no longer be used.

As a result of Dan’s work, the register can be handled in the future without fear of further damage.

Part II of “Before and After” will feature the conservation methodology for a set of three architectural drawings produced and submitted in 1867 for a competition for a Synod House that formerly was situated on the northwest corner of the St. Paul’s Cathedral property.

Much of the material for this article was supplied by Dan from interviews and a conservation report.

John Lutman is archivist for the Diocese of Huron.